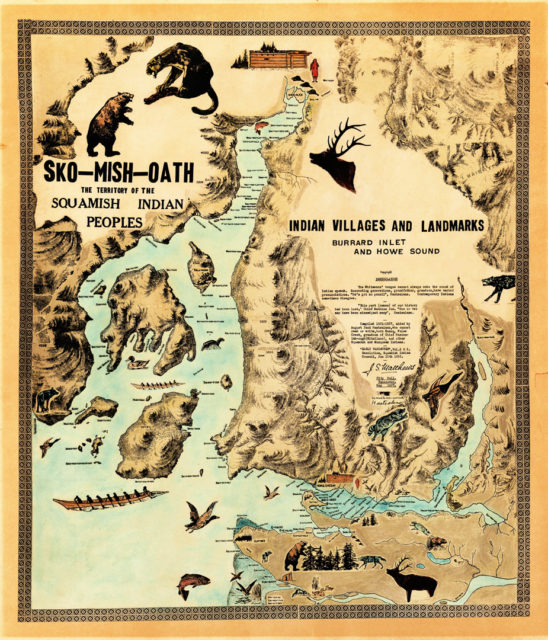

Sen̓áḵw – The Story of the Festival Site

Welcome to Sen̓áḵw

Our Festival is located in Sen̓áḵw on the ancestral lands of the Sḵwxwú7mesh (Squamish), xʷməθkʷəyəm (Musqueam) and səlilwətaɁɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) peoples. Squamish Nation Chief Ian Campbell welcomes the Bard community to this land and shares the importance of its history.

Says Chief Ian Campbell, “We believe that there are many stories of change and transformation that have occurred within this area over the history of our Squamish, Musqueam and Tsleil-Waututh people. And to continue that tradition, Bard will continue to tell stories of change and transformation, of tricksters, of triumph and love.”

History of Sen̓áḵw

Sen̓áḵw: a vibrant Coast Salish village

Bard on the Beach Shakespeare Festival is situated within the territory of Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-waututh people and sits on the site of the Sen̓áḵw village. Our respect for this place inspires us to celebrate the richness of Coast Salish history, knowledge and culture, and informs the work that we do.

Indian Encampment, Vancouver (circa 1908–1909) – watercolour by Emily Carr

Sen̓áḵw, located in what we now call Vanier Park in the City of Vancouver, was a vibrant Coast Salish village that was a place of gathering, culture, spirituality, and governance. The village was surrounded by the beauty and rich bounty of Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-waututh lands, and the people travelled by canoe throughout their great territories. Villages such as Sen̓áḵw had been major trading locations for the whole of Coast Salish territory. August Jack Khatsahlano was a prominent Squamish Chief and notable Vancouver historian who shared Indigenous oral history with others. He recorded the changes he saw around him through his interviews with Vancouver’s first City archivist, Major J.S. Matthews in Conversations with Khatsahlano.

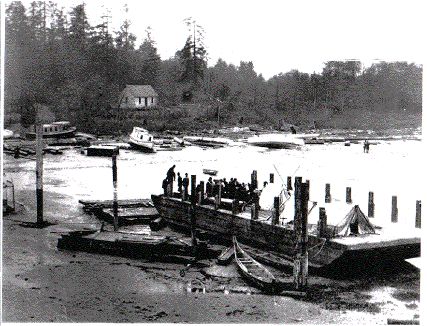

Aerial photo of Sen’ákw Indian Reserve No. 6

August Jack recounted why his great uncle, Chief Chip-kay-um, first came to Sen̓áḵw: “They from time immemorial had a fish corral there”. There was an “enormous number of water-fowl and fish available”; and “salmon still swam up the creek as far as Cedar and Third Ave., trout were caught where the Henry Hudson’s School stands, muskrats were in the swamp around Laburnum Street and smelts could be raked up Kitsilano Beach with a stick.” Beginning in the 1820s, as the City of Vancouver grew and transformed around the village of Sen̓áḵw, the areas for gathering wild cabbage, mushrooms, berries and camas lilies grew smaller. Whaling, and overharvesting of fish and other marine species in English Bay and within Howe Sound, greatly impacted the Indigenous population – along with disease, and restrictive and oppressive legislation. As the City grew, the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-waututh were forcibly removed from their villages and homes and required to live on small reserves under the control of the federal government. In 1869, Sen̓áḵw became Indian Reserve No. 6, consisting of an allocation of 37 acres of land for the Indigenous people to live on. In 1876, the Reserve was expanded to 80 acres.

1913. Removal from Sen̓áḵw Indian Reserve No. 6

Slowly, from 1886 to 1902, Indigenous peoples were removed from their traditional village sites and homes and required to live on reserves. As the City grew around them, legislation was enacted that required all Indigenous peoples on reserve be removed if the population around them exceeded 1,000 settlers. In 1913, this happened at Sen̓áḵw. A barge arrived, and the residents were instructed to board the barge to receive funds from the Indian Agent. Once everyone from the village had boarded the barge, it was pulled from the beach and set adrift into English Bay. The village was then set on fire and burned to the ground. The owner of Cates Tugs, seeing the barge drifting precariously in the Bay, went to the rescue and towed the barge to Capilano Reserve, located in North Vancouver.

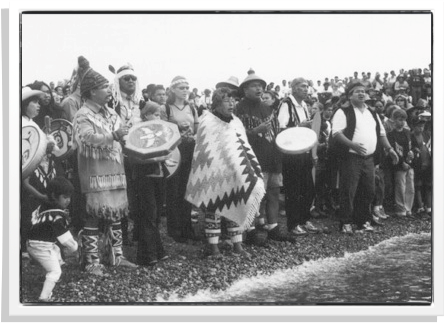

2002. Squamish celebrate the return of a portion of Sen̓áḵw Indian Reserve No. 6

What followed were years of court battles and alienation from the land and waters that meant so much to the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-waututh people. Much of the major infrastructure we see around us is situated on reserve lands. The transformation and changes within the City of Vancouver and surrounding areas have been vast and have all but erased the village and sacred sites of the Coast Salish people. The accounts in Conversations with Khatsahlano of elk, bears, and the abundance of wildlife at False Creek seem unimaginable today. Close to the original village site, underneath the south end of the Burrard Street Bridge, there is a marker. It is a Welcome Figure that was erected in 2006. Made from a 20-foot red cedar, this pole is a grandfather figure, representing strength of spirituality. The arms are raised in a gesture of welcome, which is part of Coast Salish protocol. Visitors are welcome to this place, moving forward together with one heart and one mind toward reconciliation and recognition of place and history. In 2014 the connections of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-waututh were further strengthened with a Declaration statement and signing of a Protocol Agreement, to work together, as they had always done in the past, toward sustainable futures for their membership – and to begin the process of reconciliation for all peoples.

- Welcome Figure, carved by Darren Yelton

- 2014 Protocol Agreement signing ceremony

WE ARE MUSQUEAM, SQUAMISH, TSLEIL-WAUTUTH

The three Nations of Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-waututh, encompass vast traditional territories that taken together include the City of Vancouver downtown core. Our Nations, as part of the Coast Salish families, are each connected through ancestral names, tradition, culture and spirit, just as we are connected to this land that has been our home since time immemorial. It is through these connections that we celebrate who we are as family. It is our coming together united in times of celebration and times of sorrow that we call on our traditional teachings to guide us. Our Nations have never ceded our lands and it is through the strength of our Ancestors that we unite to continue in their footsteps to create a legacy for future generations. We look to the past to guide our future, recognizing the respect and unity that comes from our teachings. It is with one voice that we awaken the names, village sites, and language of our three Nations upon this land. We share a history that is not forgotten and it is through the strength of knowing who we are and where we come from that we reinvigorate our connections. Each Nation has built on the strength of who they are and together we call on the traditions that have seen us through the changes that have been imposed upon our traditional territories. Our connection to the land is strong, coming from our spirit and traditions and we can never be separated from this connection.

Bard on the Beach is grateful to Lisa Wilcox of The Engagement Hub for her assistance in creating this page.